Science was always there for Rebecca Saive. ‘You could say that science was omnipresent in my childhood. My mom and dad were both chemists and I was fascinated by how nature does the stuff it does.’ It might have been this childlike fascination, sparked by kitchen experiments with her parents, that has led to a life of a thriving academic. ‘As a scientist, you should never lose your inner child. Children have this enthusiastic curiosity, and it helps a lot in science if you keep it.’

‘You need to feel comfortable breaking boundaries’

This ability to wonder and push outside the box is the essence of a scientist, believes the UT professor. ‘What makes a good scientist? That is a very big question and there is no single answer to it, but I believe that you need to feel comfortable breaking boundaries as a scientist. You shouldn’t just become book smart and absorb knowledge that is already there. You should try things that are not necessarily recommended by the textbook, but that you want to try - just because you need to see what happens.’

Rebecca Saive’s career in a nutshell

2023 – present Professor of Applied Physics and the head of Photonics Materials Systems for Light-Energy Conversion group (part of Inorganic Material Science), Faculty of Science and Technology at the University of Twente

2020 Named one of MIT’s global ‘Innovators Under 35’

2018 – 2023 Assistant & Associate Professor, Faculty of Science and Technology at the University of Twente

2017 - 2021 Co-founder & CTO of ETC Solar

2014 - 2018 Postdoc & Senior Scientist at California Institute of Technology (Caltech), USA

2014 PhD in Physics, Heidelberg University, Germany

An innovator

A few years ago, professor Saive was named one of MIT’s global ‘Innovators Under 35’. An ‘innovator’ indeed seems like a fitting description for the UT researcher. ‘Yes, I’d say I’m an innovator,’ she agrees. ‘I’ve never done things because they might improve my career prospects. I have always done what I thought was interesting and worth pursuing. For example, my team just published a paper basically creating a new field. I don’t think it will get cited a lot, but I don’t care about that. I never did. I care about developing something completely new, something that nobody has done before. This is something other scientists might disagree on. A lot of people would say that I should devote my energy to solving problems that are clearly identified in my field. I prefer to do things that are out of the ordinary.’

She also prefers to work on projects driven by real challenges of the world. ‘My dream is to see something I invented for the benefit of society,’ says Saive. ‘I have tried to work on projects that didn’t have a societal outlook. The physics was just as interesting, and I learnt a lot but, in the end, it was not how I wanted to spend my time. I need the societal challenge as my motivation. However, I don’t think that all scientific research should be driven by societal problems. Some big breakthroughs were made by accident, through research for the sake of research. There should be room for both, but I’m clearly on one end of the spectrum.’

‘I see running a start-up as necessary in order to create impact’

The need to transform ideas into solutions was also the reason why the scientist added ‘an entrepreneur’ to her resume. In 2017, Saive co-founded the start-up ETC Solar (now MESOLINE), a company which originally developed a micro 3D printing tool capable of printing contacts for solar cells. The company got sold in the meantime and switched its focus, but the UT professor is considering starting a new venture. ‘Although I’m not part of the company anymore, I’m really proud of it. They will take my technological innovation and develop it into a societally important application – and make real impact. If we hadn’t started the company, we would work on the innovation, publish some papers and that would probably be it. If you have a complex idea, you cannot always rely on others to take your innovation further and bring it to society. Having my own company is not my big ambition or favorite pastime. I see running a start-up as necessary in order to create impact.’

Rebecca Saive’s research in a nutshell

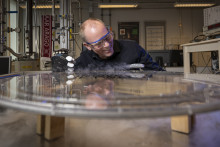

Rebecca Saive is a professor of Applied Physics with a focus on solar energy conversion, nanophysics, and light-matter interaction. She has led the development of effectively transparent contacts (ETCs), a world-record solar cell front contact technology. Other research areas include optical modelling for improved solar cell performance, materials interface investigations, and nanoscale fabrication and measurement techniques. She and her team aim to develop solar cells that are more efficient than ever before.

‘I had a childhood fascination with light and an early realization that energy is a big problem for society. And then I realized that these two are connected and could become my profession,’ says Saive. Which is why she chose to focus on improving solar cells, and contributing to a cleaner and more sustainable energy source for the world.

Professor Saive runs her own research group, which aims to improve the yield of solar energy devices, specifically solar cells. Simply put, the scientists come up with novel concepts that help to get more light into solar cells. They do this by changing the solar cells themselves, but also by modifying the surroundings of the solar modules. ‘For example, we are designing novel or improved reflectors which could guide the light from the surroundings into solar panels,’ explains Saive. ‘Imagine that there is snow all around your solar panels. It reflects a lot of light, and this light could be guided into the solar cell. We are aiming to develop a material system that is even better at reflecting light than snow. In practice, we could cover the façade of a house in this material, so that it can reflect the light onto the solar panels on your bike shed, for instance. This way we could collect more light with less panels.’

Challenged

When talking to Rebecca Saive, it is abundantly clear that she has found her calling – in her research field, but in academia in particular. ‘I am certainly in the right place,’ she confirms. ‘I really love working with students, seeing their progress. The best part of my job is that every day is very different. I might arrive at work at the same time, but other than that, each day brings something completely new. I find that very appealing. Yes, as an academic you have a lot of different tasks, but I’d rather be challenged or even over-challenged than the opposite. Moreover, it’s a very dynamic environment with a lot of passionate colleagues with a positive working mentality – which is something contagious.’

‘Scientists should have the freedom to pursue research ideas that don’t necessarily fit any funding scheme’

More freedom. That’d be the one thing professor Saive would wish for. ‘The most bothersome part of an academic career is having to constantly look for funding. I have to spend a lot of time and energy on making sure that I get funding and can therefore continue my research,’ she explains. ‘I think the government should provide money, so that each principal investigator (PI) can have at least one PhD at all times, so that we can continue our work. I agree that there should still be some competitive funding, but scientists should also have the freedom to pursue research ideas that don’t necessarily fit any funding scheme. In the end, you are the expert in your own field, and you should be able to decide what research needs to be done. Currently, you have to explain your work to people who are not familiar with your field and somehow convince them that you deserve the money. I believe it would be better for scientific output, if PIs had a certain freedom to work on crazy ideas without having to justify them.’