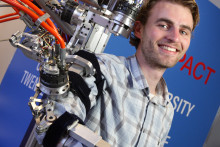

Alexander, a PhD student in the Laboratory for Biomechanical Engineering, is showing me around. He touches a screw, moves around some cables, and then illustrates that his arm can actually wear this machine. I feel like I am on the set of an adapted version of the movie I, Robot.

Limpact knows it all

‘We developed an exoskeleton called Limpact, to facilitate diagnoses and to stimulate functional recovery after a stroke,’ Alexander explains. ‘You put your arm in it and move it any way you like. The machine relieves weight, or corrects movements if necessary. Simultaneously, it measures torques in different joints and their corresponding angles.’ According to the blond researcher, these measurements make the mechanism unique compared to available alternatives, because they enable optimisation of physiotherapy. ‘Limpact is able to separate intrinsic reactions from reflexes, monitors all joints and is very fast,’ Alexander continues. ‘With this thing, you know it all. Physiotherapists no longer have to make subjective judgements on status or progress, but receive objective insight into the condition of the patient. This greatly advances the recovery plan.’

Limpact is the improved version of Dampace, which was developed in 2004 by Alexander’s supervisor Arno Stienen. That prototype was tested in Het Roessingh rehabilitation centre in Enschede for four years. Alexander: ‘It is good to know that the first prototype worked, but we also discovered flaws. Limpact runs smoother, resembles more natural movements, is able to isolate different muscle activities and is less heavy. After a true trial and error process we have now eliminated all kinds of growing pains and are ready to use this improved prototype in practice.’

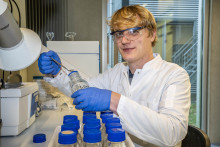

This testing will be done with help of a university student, who will connect the tests to a study on how people learn. Alexander is very happy with the assistance of students: ‘This project combines many disciplines. We have many interesting and suitable assignments for students in any field of engineering and even psychology and business administration.’

Rows of machines

When looking for a PhD position, Alexander had various options to choose from. He had good reason for making this choice: ‘I truly hope that this project will help people. That it will improve people’s quality of life. In fact, I hope that in five years from now, Limpact will have found its way onto the market. And after ten years, I am looking forward to seeing a row of these machines in rehabilitation centres.’ He adds that there are many other areas of application. ‘This technology is also suitable for people with Parkinson’s disease or transverse myelitis. And what about top athletes or the entertainment industry?’

But what about his personal ambitions? Alexander: ‘I don’t know yet if I will remain connected to Limpact for the long run. After my dissertation, anything is possible.’