Nowadays, police officers learn to interview suspects using theory and books and practicing with an actor. Using an interactive virtual suspect would improve the teaching process, as everybody could get a chance to interview multiple ‘suspects’, says Bruijnes.

Any system that interacts with a human and has its own behavior has three parts . ‘First you have to sense and interpret the behavior of the user. For instance, you can use a speech recognizer or observe the nonverbal behavior. The next step is to reason what this behavior means. For example, if somebody is aggressive, you might become aggressive towards them too. And the last part is the actual behavior realization’, explains Bruijnes.

Abstract model

Bruijnes focuses on one part of this interactive system. ‘I’m developing a mental model that stands in the middle, between the interpretation and the realization’, he says. ‘We receive abstract information such as ‘he is being aggressive or friendly’ and we perform calculations based on that. These calculations are based on psychological theories that explain behavior of suspects in real life. Afterwards, this program gives us output, which is again very abstract and can be used for the behavior realization, such as displaying an angry face on the screen and yelling at the user.’

Testing of the system

Does this program actually work? ‘We already did an interesting experiment using this abstract model’, replies Bruijnes. ‘We told the participants in the study that there are three personalities programmed into the computer. Then we let them interact with this model using abstract features – such as now I’m reacting in an angry way’ – to which the system responded in an abstract matter as well. Afterwards, the people had to guess which personality they were interacting with.’

How did this experiment turn out? ‘The initial results are promising’, says Bruijnes. ‘People got about 80% of the personalities right, which shows that our system can – on an abstract level – portray a convincing personality.’

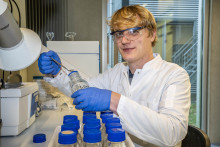

The virtual agent on the photos is created by Heleen van der Zaag.